Near Miss: Turnagain

Location: Cornbiscuit SW Face and N Face Avalanches

EVENTS

Around noon on Saturday, January 7th, several groups were out touring on Cornbiscuit ridge at Turnagain Pass. At 12:40pm, an estimated 13-15 people were either on one of two up-tracks (NW ridge, or W/SW broad ridge/face), higher along the ridge itself, and two were skiing down the SW face. At this time, a very large avalanche was triggered by a skier at the top of the SW face who was moving to a spot to watch their 2 partners descend the slope. Around 20 minutes before the avalanche, 5 people skied the slope that avalanched without incident. The events are best described by this skier who triggered the slide:

“We were a group of 3 experienced skiers and were just planning on getting some powdery laps in a spot that has been getting a lot of skier visits (I skied it a couple weekends ago). We were behind about a dozen other folks as we left the parking lot. No noticeable signs of instability other than the large releases that were listed in the avy report. We followed the ski track up the NW ridge/face. I generally hate that route due to all the thin spots that could trigger something and usually prefer to go around and up the SW side. But we saw many folks headed up and no signs of any releases, so we followed the established route. No issues or red flags on the skin up.

Once we got to the final flat spot before the summit ridge, we stopped and decided NOT to follow the half dozen or so people that kept climbing and heading further back on the Cornbiscuit ridgeline. Again, we were just going to get a quick powder lap in on the SW face to see how things felt. I made a couple turns down the SW ridge/roll and stopped to take some photos. My friends then skied by me for a quick snap and continued down the slope. I put my phone away, put my gloves back on, grabbed my poles, and then made one more turn on the ridge to reestablish a line of sight to my partners as they descended.

Sliding to a mellow stop where I got eyes on my buddies, the slope cracked 18” downhill from my skis and the crack ran rapidly in both directions. I saw the entire snowpack, down to the ground, begin to slide. I yelled ‘avalanche’ repeatedly, but my friends were way too far down the slope to hear anything. However, people on the skin track did hear me shouting. I didn’t move while I kept my eyes on both my partners. One member broke skiers right and only got hit by a bit of the powder cloud. He was able to yell ‘avalanche’ just before that and the second skier heard that shout and broke skiers left away from, what he thought was the main slide. Unfortunately, he turned back toward the bulk of the debris and was immediately hit by the avalanche. I had eyes on both skiers until the powder cloud obscured my view of the bottom of the entire run.

Once the powder cloud passed, I assessed where I was standing and whether or not it was safe to begin my visual search and ski towards the last known point for the second skier. Since it released to, basically, the ground, I felt that it was safe to ski the bed surface. I began shouting to everyone on the skin track to get their beacons in search mode and not ski anything in the area while I was looking for my friend. The second skier lost his gear after getting hit by the powder blast and began tumbling in the main part of the slide. He was only carried 30-50 meters as he was already almost down at the alders when the avalanche struck him. He had a beacon, shovel, probe, but no airbag. He managed to swim to the surface while things were moving and then came to the top of the debris, spitting out a snow plug, just as the snow stopped and he came to rest. I was about halfway down the slope when I saw him stand up. I shouted and he replied with the “ok” hand signal. I shouted to everyone on the skin track that both my partners were accounted for. I continued to ski down to aid the second skier as I assumed he had lost all his gear. We did a quick medical check and he seemed to be ok but sore and bruised, so I immediately gave him one of my skis and we one-skied it back out to the car. Back in the parking lot, we saw another group return a bit later and mentioned they had done an additional beacon search and someone had located the missing pair of skis. We discussed what happened with them and then thanked everyone for returning the skis.”

After the avalanche, when the two skiers on the slope were known to be safe, around 7 people from other groups initiated a beacon search of the debris in case there was an unknown person(s) caught. No signals were found and after speaking to the groups in the area, that all persons were accounted for. The debris covered portions of the W/SW up-track. No one was on that part of the up-track at the time of the avalanche.

This avalanche sympathetically triggered another large slab avalanche on the north aspect of Cornbiscuit, unknown to those on the SW side of the ridge. Similarly, those on the north side did not know there was an avalanche on the SW side, as both were well out of view of each other. Debris from the north side avalanche covered a well used up-track. A group of two had just crossed the area where the debris ran over the track and the person in the rear pulled their airbag as the powder cloud engulfed them, but no debris. Another group was on the lower NW Cornbiscuit ridge and watched this avalanche occur. Likewise did another group across the valley that was on the lower slopes of Magnum ridge. This group on Magnum had just crossed the same area a bit earlier.

Higher, along the Cornbiscuit ridge itself, there was a group that felt the collapse and saw two portions of the crown on the northerly side appear. They heard shouting behind them and turned around, heading back down the ridge. They noted many cracks along the ridge and became aware of the avalanche on the SW side.

AVALANCHE INFORMATION

Type: Hard Slab

Problem/Character: Persistent Slab

Crown Thickness: 2.5-4′ (80-120 cm). Deeper pockets were close to 6′ deep.

Width: 900 feet

Vertical Run: 1,000 feet

Trigger: Skier (unintentional)

Weak Layer: Facets between two crusts

Aspect: SW, propagating around a west face and releasing another large slab on a N aspect.

Elevation: 2,800 feet

Slope Angle: 35-40 degrees

Code: HS-ASu-D3-R3-O

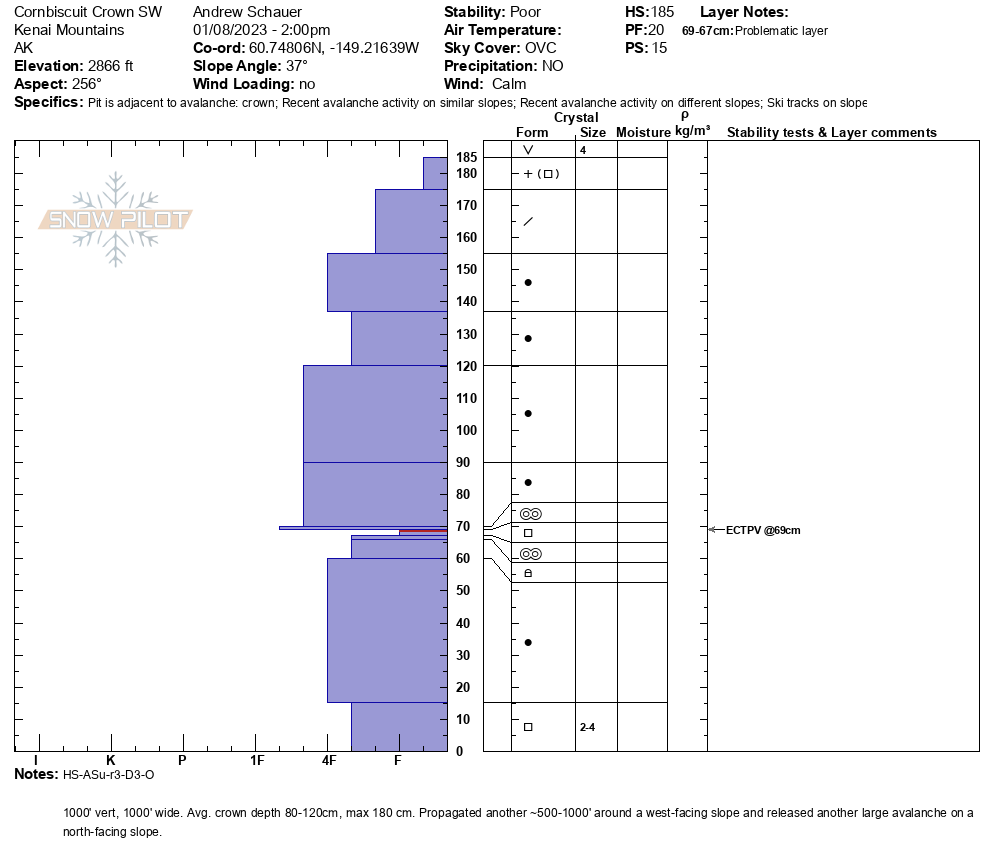

The avalanche failed on a fist-hard layer of facets sandwiched between two melt-freeze crusts. This would be just below the uppermost crust of the Thanksgiving crust/facet layer that the CNFAC had been watching as a layer of concern since the first week in December. The avalanche also pulled out several pockets down to the ground as it ran. We found fist-hard 2mm facets on the ground at the crown. We did a quick ECT at the crown of the avalanche that released on the southwest aspect and got an ECTPV, with the column popping right out of the pit while being isolated, failing on the same layer that the avalanche failed on.

WEATHER AND SNOWPACK

The weak layer the SW face avalanche failed on, as well as what we believe the N side avalanche also failed on, formed as a result of weather events starting in mid-November. A strong inversion during a four day stretch between 11/14 and 11/8 brought above-freezing temperatures into the alpine, forming a melt-freeze crust up to 3000′. Following this warm spell, a warm storm on 11/19 brought mixed rain and snow up to 2500-3000′ with .8″ snow water equivalent (SWE). Meltwater percolation and fluctuating rain/snow lines during the storm created a series of saturated layers in the upper snowpack, which were buried by a dusting of cold, dry snow on 11/21 and a more significant precipitation event between 11/22 and 11/24, with another .8″ SWE equaling over a foot of snow. We continued tracking the melt-freeze layer from the warm spell and the 11/19 storm following this loading event, following the evolution from alternating crusts and rounded grains to alternating crusts and facets. We first identified the crust/facet combination as a layer of concern in the first week of December, and had continued monitoring it as a layer of concern right up to this avalanche event.

The loading event that led to the avalanche began on Christmas night, when a warm system brought 1.5-2″ SWE in 24 hours, equaling 1.5-2′ of snow, with at least some rain reaching up to around 2500′. The next major load came on New Year’s Eve, with 2.5″ SWE in 48 hours. In addition to these two stronger pulses, there was intermittent light precipitation between 12/26 and 1/3, totaling just over 5″ SWE between Christmas and 1/3. We saw multiple storm slab avalanches during this period, but activity on deeper weak layers was very limited. The weather picked up again overnight on 1/3, with another system bringing 1.4″ SWE by the end of the day on 1/4. This storm was accompanied by strong easterly winds, with sustained speeds of 30-40 mph and gusts as high as 74 mph on nearby ridgelines. This final loading event would prove to be the one that tipped the scales, setting off a widespread natural cycle with avalanches failing within the new snow as well as on the deeper Thanksgiving crust/facet combination. A group on snowmachines triggered multiple large avalanches remotely on 1/5 less than 5 miles from where this event would occur two days later.

AVALANCHE DANGER

The avalanche danger was rated MODERATE for the day the avalanche was triggered, noting ‘Triggering a very large avalanche on a buried weak layer 3-6′ deep is possible. We have seen widespread avalanches on deeply buried weak layers this week, including many human triggered avalanches that were remote triggered from low angle terrain adjacent to steeper slopes”. The full forecast is available HERE. Due to the size and unique ability for a large avalanche to propagate and release another large avalanche over a ridgeline, the center increased the danger to CONSIDERABLE the following day. It would be a case where the likelihood may have been more in line with moderate danger, but because of the unusual nature of the snowpack the best travel advice was in line with ‘cautious route finding and careful decision making’– straight out of the considerable level on the North American Danger Scale.

Crusts and facets are no stranger to Turnagain Pass. There have been many large avalanches in the past on the SW face of Cornbiscuit. Some have been triggered by people after several tracks were on the slope, as in this case, consistent with buried persistent weak layers. Unique in this instance is that two avalanches were triggered by the same collapse, one on either side of a prominent ridge. Here are a couple older reports:

December 13, 2008 – Human triggered, skier buried 5ft deep, rescued: https://www.cnfaic.org/accidents/cornbiscuit/

March 11, 2010 – Human triggered, no one caught: https://www.cnfaic.org/observations/cornbiscuit-15/

February 18, 2020 – Natural cycle: https://www.cnfaic.org/observations/turnagain-pass-skier-side-sunburst-magnum-cornbiscuit/

We would like to sincerely thank the skiers involved, and the other groups in the area, for sharing their information and photos. Understanding events like this can help all of us have safer days in the backcountry in the future.

Report compiled by Chugach NF Avalanche Center staff.

Contact: staff@chugachavalanche.org

Google Earth map showing the outline of both avalanches (SW face avalanche and N face avalanche).

Wide angle view just after release

SW broad ridge/face up-track, a portion was taken out by the slide

Trigger point, red circle and photo by skier who triggered the avalanche

Investigating the crown on the SW avalanche the day after the event. Photo: Matti Silta 01.08.2023

Powder Cloud

A zoomed in section of the top of the crown

Flank of avalanche and crown

Avalanche seen from lower in the debris

View of avalanche from near the partial burial location

North aspect avalanche and up-track entering debris

Looking down at the north side of the avalanche debris with the party of two beyond

Precipitation leading up to the event. Taken from the nearby Turnagain Pass Snotel site. Daily danger ratings are shown in the colored bar along the bottom of the plot, colored by the highest danger for the day. Gray shaded bars in the background represent night hours, and the daily breaks are marked at 0600 to correspond with the timeframe of the danger ratings.

Detailed snowpack information from the crown of the avalanche on the SW aspect, taken the day after the avalanche. 01.08.2023

Snowpack information near what would become the looker's left flank of the avalanche, three weeks before the avalanche happened. It is noteworthy that the same layer that would produce this avalanche was showing signs for concern in multiple snowpits in the immediate area weeks prior to the event. Snowpit from 12.18.2022